Increasing patronage is key to achieving the UK’s zero-emission bus transition

In a recent Sustainable Bus article (February 2023 issue) looking at how the UK is funding its zero-emission bus transition, a conclusion was that to achieve it, increasing patronage is crucial. Confidence in long term passenger demand on bus travel is necessary to give the security in required ZEB (zero-emission bus) technology investment. Although passenger numbers are rising, patronage is yet to return to pre-covid levels.

Below, an article published on February 2023 issue of Sustainable Bus magazine.

By Alex Byles

In a recent Sustainable Bus article (February 2023 issue) looking at how the UK is funding its zero-emission bus transition, a conclusion was that to achieve it, increasing patronage is crucial. Confidence in long term passenger demand on bus travel is necessary to give the security in required ZEB (zero-emission bus) technology investment. Although passenger numbers are rising, patronage is yet to return to pre-covid levels.

UPDATE 18TH MAY: The government has announced more support for England bus fares with the £2 flat fare continuing until end October, when it will then rise to £2.50, with additional government budget then provided

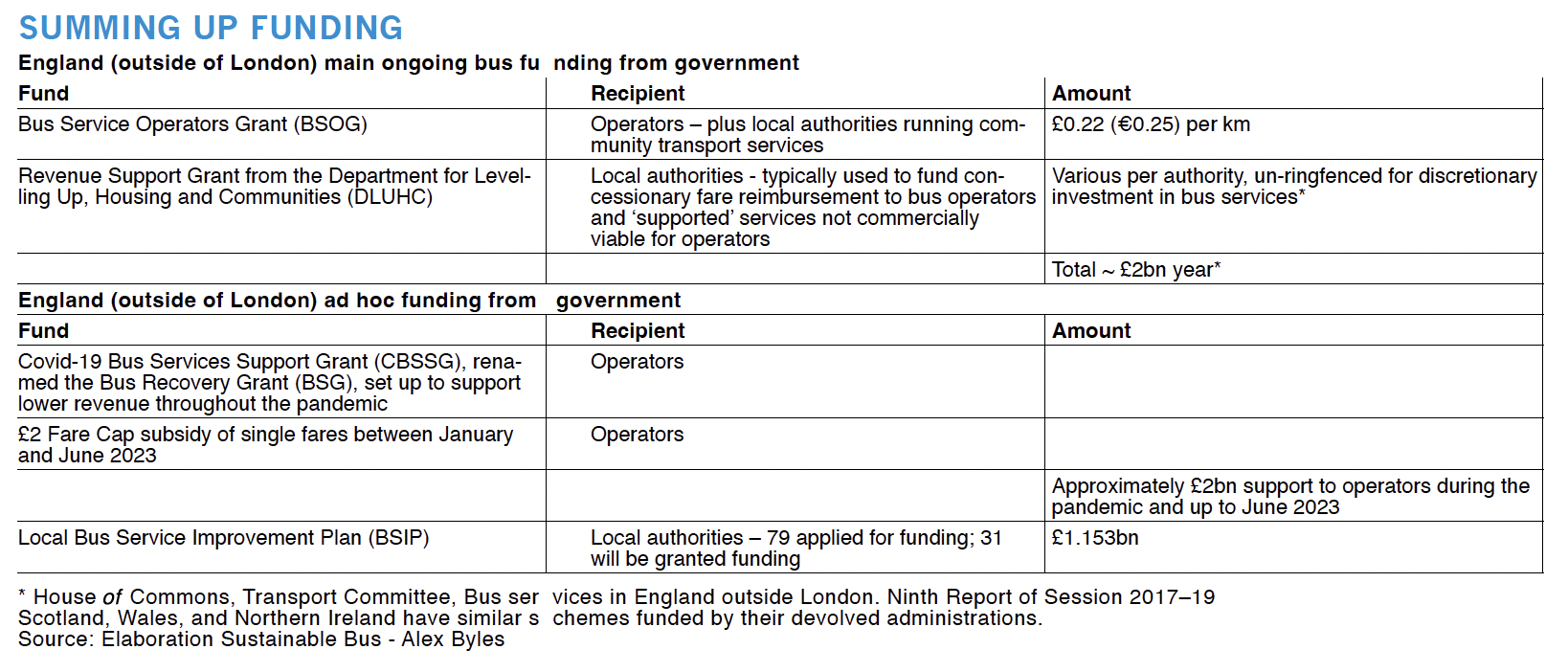

The UK government has stated the aim of increasing patronage, including its March 2021 launched “Bus Back Better: The National Bus Strategy”, supporting England outside of London with ad hoc grants, as well as more established longer-term funding, while devolved regions manage their own support.

Outside of London, the UK bus network is mainly privatised, with bus operators generating around 60 percent of their income from fare-paying passengers, with public funding subsidising the remainder, according to data from National Audit Office. As a result, services that are commercially unviable, or unable to be funded by local authorities, are at risk.

Zero-emission buses have a role to play in improving patronage. As well as the incentive of sustainability, they’re clean, quiet, and the ride is more pleasurable. But whether it’s a zero-emission bus or a diesel bus, if it’s stuck in congestion, it’s not going to increase patronage. Capital funding to zero-emission buses is crucial, but if that doesn’t come alongside a proper bus service improvement plan with defined routes for bus priority, the benefits that ZEBs offer might not be fully realised.

Tim Griffen, project officer, at Zemo Partnership

No legal requirement

The Campaign for Better Transport estimates that operator commercial services declined by 26 percent between 2012 and 2020 – albeit most significantly in the pandemic’s first year – and services supported by local authorities declined by 52 percent in bus miles over the same period. “There is no legal requirement to supply a bus service and no framework is provided to guarantee a bus service to those who need it. For patronage to grow, people need to feel confident that they can switch to using buses for most of their journeys, and that services will still be there in future. This is not the case in many areas,” says Claire Walters, chief executive, Bus Users UK, that champions the rights of passengers.

If bus services aren’t sufficient, the current system can allow local authorities to take control, like developments in Manchester. Later this year, the city will become the first outside of London to have a regulated bus system. While the regulation debate has continued since privatisation in 1985, the existing framework can be successful in increasing patronage.

Privatization, franchising, partnerships

“With close partnership, we can get to a non-adversarial culture between the private and public sectors which exists in places like Oxford and Brighton, where privatisation has worked relatively well. Franchising in certain areas can be appropriate, but many authorities are concluding that effective partnerships can be a preferred way forward,” says professor Graham Parkhurst, director, Centre for Transport and Society at University of the West of England, Bristol.

But whichever approach, greater stability in financial support is necessary to enable reliable service provision long term.

“There’s a marked contrast with rail, which has had relatively high levels of security and funding, despite buses carrying significantly more people,” says professor Peter White, expert on public transport systems, University of Westminster. “The bus industry has had repeated three-month budgetary extensions, meaning that management has had to prepare for sharp service cutbacks, then to discover that they can carry on running for another three months. That’s a highly unsatisfactory way of proceeding.”

Reliable journey time

The Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT) reports that for every 1 percent bus speeds decrease each year, this results in over 10 percent fall in passenger numbers over the course of a decade. The organisation says congestion is the number one challenge to a reliable bus service and is the main reason people do not take the bus, making journeys too slow with unpredictable timings.

According to CPT, measures including priority at junctions and traffic lights, bus-only roads, bus-only lanes, and park and ride schemes, have helped increase patronage, in combination with other factors, by as much as 50 percent in Bristol and 24 percent in Milton Keynes. However, prioritisation at the expense of the car can still face resistance. Though Coventry plans to become the UK’s first all-electric bus city, a proposal to introduce bus gates on certain city centre streets, with private cars prohibited between 10am and midnight, has just been rejected following fears of declining trade from local shops.

With close partnership, we can get to a non-adversarial culture between the private and public sectors which exists in places like Oxford and Brighton, where privatisation has worked relatively well. Franchising in certain areas can be appropriate, but many authorities are concluding that effective partnerships can be a preferred way forward

Professor Graham Parkhurst, director, Centre for Transport and Society at University of the West of England, Bristol.

Service reliability decreased by extended dwell time can also be a challenge. Outside of London, a single door for entry and exit, as well as diverse fares and payment methods, impact process speed. As well as improvements to reliability, service frequency is also important.

“In the late ‘80s with high frequency minibuses, we were able to show that a minibus every 10 minutes, instead of a double decker every half hour, produced a large increase in ridership, purely as a frequency effect,” says Peter White. “With the driver recruitment challenge, this isn’t feasible at the moment, but with driverless buses, this might change, depending on the issues connected with automated vehicle technology.”

Inter-urban and rural networks

Connecting two or more towns or cities, inter-urban bus services provide a link with intermediate stops to serve villages en route, with these services able to provide connections currently missing from the rail network.

“Inter-urban bus services showed they can be successful in attracting more riders to buses on a purely commercial basis, and even those with some government finance achieve it at a relatively modest cost,” says Peter White. “In rural Wales, for example, the Traws Cymru network is very useful for filling gaps in the rail service, especially for north-south movement, and public sector support is modest compared with the cost of rural rail services.”

Similarly, for rural areas, Graham Parkhurst argues in favour of a “hub and spoke” system, including frequent routes with bus priorities where necessary, fed by connectors including demand responsive links. If necessary, car parking can be used too, which would still minimise environmental impact and congestion.

There’s a marked contrast with rail, which has had relatively high levels of security and funding, despite buses carrying significantly more people. The bus industry has had repeated three-month budgetary extensions, meaning that management has had to prepare for sharp service cutbacks, then to discover that they can carry on running for another three months. That’s a highly unsatisfactory way of proceeding.

Professor Peter White, expert on public transport systems, University of Westminster

“Rural services are unlikely to be commercially profitable, but we have to accept that public transport is a good for the economy and society, and it needs financial support,” says Graham Parkhurst.

“One important issue is whether you can integrate the public bus service with the school transport provision, because authorities have a statutory obligation to provide free school travel above certain distances, whereas they are not obliged to support buses,” says Peter White. “Inevitably, rural service frequencies will be lower, but integrating these functions could achieve the most efficient use of public money.”

“Clearly, it’s difficult to provide services which are free from any form of subsidy in rural areas because the passenger numbers are quite low,” says Martin Dean, managing director, UK regional bus, Go-Ahead. “But where you’ve got a transport authority that’s willing to invest, I think you can have a successful network in a rural area. Cornwall is a really good example. I would say the level of bus provision there is probably the best it’s been for a long time and we’re happy to contribute to that.”

Environmental sustainability

To meet net zero climate targets, buses can more quickly increase modal share than rail, based on an already available road network. At the same time, incentivizing a switch to electric cars could be a problematic long term strategy.

“Switching to electric power for private cars presents some efficiency benefits, but it’s likely to be a long time before we have a fully decarbonized electric grid. An electric car still needs as much road space as a diesel or petrol variant, so they will still impose congestion on the economy,” says Graham Parkhurst.

“Zero-emission buses have a role to play in improving patronage,” says Tim Griffen, project officer, at Zemo Partnership, that works to accelerate transport to ZE. “As well as the incentive of sustainability, they’re clean, quiet, and the ride is more pleasurable. But whether it’s a zero-emission bus or a diesel bus, if it’s stuck in congestion, it’s not going to increase patronage. Capital funding to zero-emission buses is crucial, but if that doesn’t come alongside a proper bus service improvement plan with defined routes for bus priority, the benefits that ZEBs offer might not be fully realised.”

Fare price policy on

In recent attempt to increase bus use, the government is subsidising a temporary flat £2 (€2.27) charge for a single journey, operating between January to June 2023. CPT says the interim results are mixed, and according to an April report by Transport Focus, an independent watchdog, 11% of bus users say the £2 bus fare has increased their bus use, up from 7 percent in January.

“The £2 flat fare has meant that we’ve seen some pretty significant patronage increases on longer distance routes, with growth in some cases up to 40 percent,” says Martin Dean. For example, Go North East’s X10 service between Newcastle and Middlesborough, a distance of 39 miles (63km) is usually £8 (€9), giving passengers a significant saving.

While Go-Ahead Regional Bus is now at just over 90% patronage, the operator notes the UK trend of a slower return of concessionary passengers – despite their receipt of free travel on reaching pension age. Professor Jon Shaw, University of Plymouth, who specialises in the geography of transport, travel and mobility, argues that replacing free concessionary travel with a 50p flat fare for all could increase patronage and revenue.

“Instead of providing free travel for older people, and under 22s in Scotland, charging a flat fare of 50p still provides subsidized transport, but the money that you free up can be returned to the bus system for the benefit of everybody, funding the infrastructure needed to increase patronage.”

Jon Shaw first published this proposal in 2014 with colleague Iain Docherty in “The Transport Debate”. Allowing for inflation from time of writing, the costing stated that the introduction of a flat fare of 50p (€0.57) per single journey would free up more than £500m (€569m) a year for investment. This would make it possible, they argue, to roll out state-of-the-art, European style bus service quality across the equivalent of up to 20 cities the size of Plymouth (250,000 inhabitants) within 10 years.

Reliability is king

“We’re not talking about needing to change everyone’s travel habits straight away,” says Jon Shaw. “Change 20 or 30 percent of people’s travel habits and it gets better for everybody. What’s key is providing a realistic alternative to enough car journeys to make a difference, instead of trying to provide an alternative for everything.” “If you’re trying to attract car users, I think it’s absolutely essential to make sure you offer reliability as the starting point, ahead of the more subtle issues like the appeal of electric vehicles,” says Peter White.

This is supported by the view of bus users on the ground, where confidence in the ability to quickly get from A to B reigns supreme. “If public transport is not reliable, quick, and easy to use, people are going to be wedded to their cars, even if it costs them money,” concludes Claire Walters.